How To Win CCDC

A recollection of every strategy and philosophy that took me as far as one can possibly go in CCDC, paired with honest critiques and observations regarding the competition itself.

Preface

Before I begin this post, I want to acknowledge the privileges I had during my time competing in CCDC. When I joined, our club had already built a strong relationship with NUCC, who provided us with ample infrastructure. Our Office of IT had also given us network space and direct internet access. Additionally, I didn’t need to work during the school year to support my education. I recognize that these factors gave me some inherent advantages. The goal of this post is to help level the playing field and share resources with those who may not have had the same opportunities.

Introduction

Hello, I’m Akshay, known online as “hypernova”. I’m currently a rising junior at the University of California, Irvine studying computer science. I was a two-time National Collegiate Cyber Defense Competition (NCCDC) finalist, and was the captain of the winning team for the 20th NCCDC season. Some of you might remember me from my older post: How To Win CyberPatriot.

While my time competing was short, I managed to defeat many of the competition’s top teams and win the national title. In my second and final year competing, I placed first in every competition round I competed in. My team and I are not inherently more talented or smarter than any of the others we played against, but we played to our strengths, learned the CCDC meta, and dedicated hours upon hours to ensure victory.

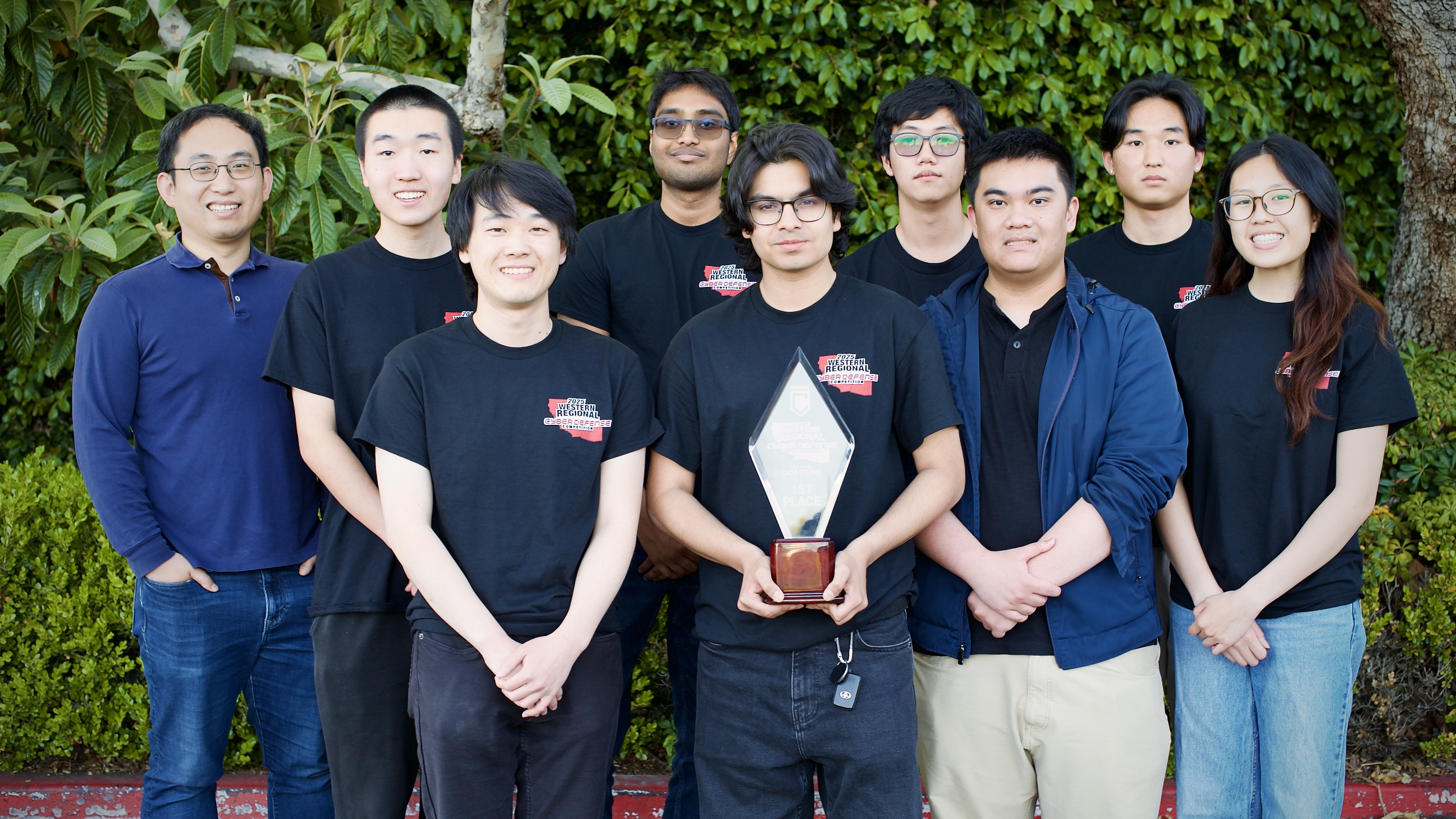

The 2024-2025 UCI CCDC Team

2023-2024 Competition Season

| WRCCDC Qualifier | 3rd |

|---|---|

| WRCCDC Regionals | 2nd |

| NCCDC Wildcard | 1st |

| NCCDC Finals | 4th |

2024-2025 Competition Season

| WRCCDC Qualifier | 1st |

|---|---|

| WRCCDC Regionals | 1st |

| NCCDC Finals | 1st |

README (important)

Disclaimer

I competed in the Western region for CCDC this season, so most of my technical advice and experience I will mention throughout this post will be heavily influenced or even tailored for WRCCDC. However, many of the underlying concepts and fundamental strategies to succeed should work across regions.

There’s no step-by-step guide to reaching the top of the competition. Instead, it’s up to individual teams to interpret this advice and adapt it to their own strategy and unique circumstances. The path to victory isn’t as standardized or clear-cut as it was for CyberPatriot, which is why I chose not to include a “Zero to Hero” section like I did in How to Win CyberPatriot.

How to Read This Blog

This post is long, and a lot of it is made up of anecdotes that aren’t always immediately actionable. I think they make the blog better, but if you just want advice you can use right away, look for section headers marked with a 🔧. Sections that are primarily anecdotal will be marked with a 📖.

When a section is marked, you can assume all of its child sections follow the same type unless explicitly labeled otherwise. For example, everything under “CCDC Is Not What You Think It Is” is marked as 🔧 actionable and important to read, but the “Captainship” subsection under it is marked as 📖 anecdotal.

If a section does not have a clear marking, I recommend reading it.

CCDC Is not What You Think It Is [🔧]

Multiple times throughout my experience competing in CCDC, I’ve been told by everyone from fellow competitors to even competition organizers that CCDC is fundamentally an incident response (IR) competition. What is often described as the intended way to play is to deploy a mobile SOC, install logging agents across the network, configure them for centralized logging, deploy a SIEM solution, and be well-versed in OS-agnostic forensics to dig up and reconstruct exact attack paths. From there, you reactively apply security controls or patches to services and systems to prevent further attack. This also includes identifying and removing any persistence mechanisms your attackers may have left behind.

However, CCDC is NOT an IR competition, it is actually active defense. Active defense means engaging the adversary during the attack, whereas IR is the process of responding to an incident after the damage has already been done or once responders have been notified of the incident. CCDC challenges teams to defend against ongoing threats that begin in real time. You are actively trying to detect, disrupt, and deny the red team while they operate. The structure of the competition supports this, as blue and red teams are interacting continuously throughout the event.

Approaching CCDC as an active defense competition rather than incident response changes the way you play and your priorities. Instead of prioritizing centralized logging and deploying a SIEM you focus on immediately hardening your systems, filtering potentially malicious network traffic, and disabling obvious attack vectors. Chasing forensic evidence while your domain is being pwned to the moon wastes time, active defense at least keeps you on track. The effort required to play with an incident response strategy is not proportional to its effectiveness in the competition.

Note that this is assuming no red team pre-plants, incident response might be more viable in a region like Southeast CCDC (SECCDC) where malware is baked into the default competition environment.

CCDC Is Easy

CCDC is secretly an easy competition. The technical skill ceiling for the competition is not impossible to reach, even if you might be competing against some of the brightest students across the country. These competitors have done security internships at major companies like Palo Alto Networks, Microsoft, and OpenAI, and some have even discovered major vulnerabilities in real software like Gradescope.

On paper, it makes no sense for my team to have won this year’s CCDC. No one on the team had played CCDC for more than two years, with four members experiencing their first season and three having never done anything cybersecurity-related just a year ago.

CCDC isn’t actually easy, but the winners aren’t necessarily the most technically skilled. Most of the top teams at the finals, and in highly competitive regions like Western and Southeast, have already surpassed the technical skill ceiling needed to succeed. After you surpass that ceiling, winning comes down to strategy, operational excellence, and most important of all, execution.

Once teams pass a threshold, more technical skill doesn’t necessarily translate to higher placement. I’d argue that my team wasn’t even close to the most technically advanced at Nationals, let alone even our own region. However, what gave us the edge was strategic decisions and effort.

This next section outlines the key strategies and mindsets I employed for my team throughout our time competing. In my experience, these are what truly separate the top teams from the rest.

Priorities [🔧]

When you get thrown into the competition environment, there are usually a LOT of things wrong.

- Domain controller vulnerable to Zerologon

- Every system uses the same leaked credential set

- Outdated WordPress site with multiple high-severity CVEs

- Custom-built site vulnerable to UNION-based SQL injection

Notice something about those bullet points: the vulnerabilities I list become increasingly more complex to exploit. I began with mentioning an unauthenticated, remote domain takeover using Zerologon and ended with a UNION-based SQL injection that takes more time and effort to even discover. But it’s not just the complexity that changes, the impact does too. Zerologon gives an attacker instant control of your entire network, while the SQL injection may not even lead to remote code execution.

This shows that there is a relevant relationship between exploit complexity and impact. The most dangerous vulnerabilities are the ones that are easiest to exploit and have the potential for major impact. This relationship provides a practical framework for deciding what to fix first. Your vulnerability remediation strategy should be guided by this relationship. Focus on the simple, high-impact attack vectors before anything else.

Mathematical Representation

You can, to an extent, represent this mathematically to better understand what your priorities might be. Consider the following equation:

\[Priority \ Score = \frac{Impact \cdot Exploitability}{Remediation \ Cost + 1}\]Each variable in the formula can be interpreted as follows:

- Impact = How bad is it if this gets exploited? (1–5 scale)

- Exploitability = How easy is it to exploit? (1–5 scale; higher = easier)

- Remediation Cost = How hard is it to fix? (1–5 scale)

Example Scoring

| Vulnerability | Impact (1-5) | Exploitability (1-5) | Remediation Cost (1-5) | Priority Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EternalBlue | 4 | 5 | 1 | 10 |

| Default Credentials | 5 | 5 | 3 | 6.25 |

| Exposed Cockpit Instance | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4.5 |

| Authenticated Local File Inclusion | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0.8 |

Scoring Rationale

EternalBlue: It scores high on both impact (4) and exploitability (5) because it’s an unauthenticated remote code execution vulnerability that is well-documented. Its remediation cost (1) is very low, as disabling SMBv1 with a single PowerShell command is enough to remediate the vulnerability.

Default Credentials: Scores high on impact (5), even above EternalBlue, because it affects virtually every single system and web application, rather than just specific vulnerable Windows hosts. Exploitability (5) is maxed out, an attacker can simply using a remote access method like SSH or RDP with a default credential set to gain high-level access to any system. Remediation cost (3) is higher than others due to the operational complexity of rotating every credential across the network and ensuring all systems or services use strong, unique replacements.

Exposed Cockpit Instance: While not as dangerous as the above, an authenticated web interface to system internals can still be dangerous, especially if the default credentials are not changed. It scores moderate across all metrics (impact 3, exploitability 3), but easy to disable (remediation cost 1).

Authenticated Local File Inclusion: Scores low on impact (2) because it typically only allows access to limited file content and requires a valid login to exploit. While it could potentially expose sensitive configuration files, it doesn’t necessarily lead directly to full compromise. Exploitability (2) is also low since the attacker must already be authenticated, reducing its immediacy as a threat. The remediation cost (4) is high because fixing LFI often requires ` modifying the web application’s source code, which is very time-consuming.

This equation and its parameters are completely arbitrary and not grounded in any mathematical research or science. It is simply to help teams reason about which vulnerabilities to fix first based on exploit complexity and potential impact.

You can generally build a well-prioritized checklist based on this relationship as you identify more vulnerabilities, and even use it ad hoc during the competition to assess how critical each issue is. The next step is to prepare strategies to reduce exploitability, impact, and remediation cost for the vulnerabilities you’ve identified.

Reduction

Once you’ve prioritized vulnerabilities based on exploitability, impact, and remediation cost, the next step is to actively reduce each of these factors.

Reducing Exploitability

The goal of reducing exploitability is to make it more difficult for the red team to actually exploit these vulnerabilities. For example, a major vulnerability that affects almost every team that plays CCDC is ZeroLogon. ZeroLogon is an unauthenticated, remote privilege escalation vulnerability against domain controllers that allows attackers to reset the machine account password to an empty string and gain domain admin access.

Downloading and installing Microsoft’s ZeroLogon patch takes time, and in some cases may even require system reboots that cause downtime for critical services. Instead of approaching this vulnerability with the goal of fully patching it during competition, we can significantly reduce its exploitability by blocking inbound Remote Procedure Call (RPC) traffic on port 139 from the public internet. This ensures that only internal systems can reach the domain controller over RPC, forcing the attacker to first compromise another internal machine before they can even attempt the exploit. They must install their tools, set up proxying, and then perform lateral movement to reach the vulnerable domain controller. This extra effort introduces friction and buys time to respond and fully patch the vulnerability. It also immediately reduces its exploitability, lowering its priority score.

Reducing Impact

The goal of reducing impact is to limit the damage an attacker can do after they’ve exploited a vulnerability. Usually in CCDC, this means making sure that even if the red team successfully compromises a service, they don’t have full root access or network takeover capability.

For example, consider a situation where the red team finds credentials for a domain user. In many CCDC environments, domain users permissions are configured poorly, sometimes with hundreds of users allocated as domain admins. If you can begin the competition by de-privileging all domain admins except built-ins like “Administrator” you can significantly reduce the impact of red team compromising one of these users. Even if they gain access, they still need to go through the next steps of finding and using a privilege escalation vector to plant persistence or laterally move. This not only buys time to rotate domain user credentials, but also reduces the immediate impact of the compromise, which in turn lowers its priority when assessing what to fix next.

Reducing Remediation Cost

Reducing remediation cost is key to staying operational during competition. It makes high-severity vulnerabilities easier to patch. While this might increase their priority score, that’s actually a good thing! If something is easy to fix and dangerous, it should be the first thing you take care of anyway.

For example, take default user credentials. If you can automate the rotation of root or user passwords across multiple machines quickly, the remediation cost drops significantly. That in turn pushes it up your priority list, since it’s both easy to fix and critical to address.

Reducing remediation cost largely depends on scripting and automation, which I’ll cover soon.

The Perfect Start

Most of the effective defense must happen early, ideally before the red team gains any foothold. In an ideal world, a perfect start means that all high-priority vulnerabilities are effectively and efficiently addressed within the first one to two hours of competition, with the most critical ones resolved in the first five to ten minutes. There are many ways to achieve this, including finding the monkey (robust inventory capabilities), automation, a well-balanced team composition, and more. We’ll cover each of these in the next few sections.

Finding the Monkey [📖]

Imagine you’re in a pitch-black room with a flashlight, and you only get one pass through. Somewhere in the dark, there might be a monkey. You don’t know if it’s there, but if you run into it, things are going to go badly. If your flashlight is small, you could miss it. If your flashlight is large, you’re more likely to see it in time.

In CCDC, the monkey is that hidden dependency, an exposed PII sink, or a critical service you didn’t realize mattered. The flashlight is your inventory strategy. Without a wide enough beam: network scans, system identification, and service enumeration, you’ll miss the monkey. Maybe it’s a database that three different services rely on, a bind account that multiple systems use, or an exposed file server sharing internal documents. If you change something blindly, you’ll trip over the monkey and take down half the network.

The bigger beam will inherently take more effort to setup and pull of. Similar to how wider inventory will cost more time upfront. However, you only get one “grace period” before the chaos fully begins. The wider your beam, the better your odds of catching the monkey before it causes trouble.

small flashlight vs big flashlight

The incredible analogy is the courtesy of Tanay Shah (Altoid0)

What’s Important?

Do you need to inventory absolutely everything and anything? You could, but you run the risk of having too much data to make sense of. The full process list from every system on the network might be useful in some scenarios, but it would be difficult to quickly extract meaningful information about dependencies and network intricacies.

Instead, I recommend a methodical process for finding the most important information about your network. Start with these two definitions:

- Scored Services: Services that are scored for uptime (e.g. alpha-http, omega-SSH)

- Critical Services: Services that are either scored, or dependencies for scored services (e.g. database server for alpha-http or the Active Directory authentication for omega-SSH)

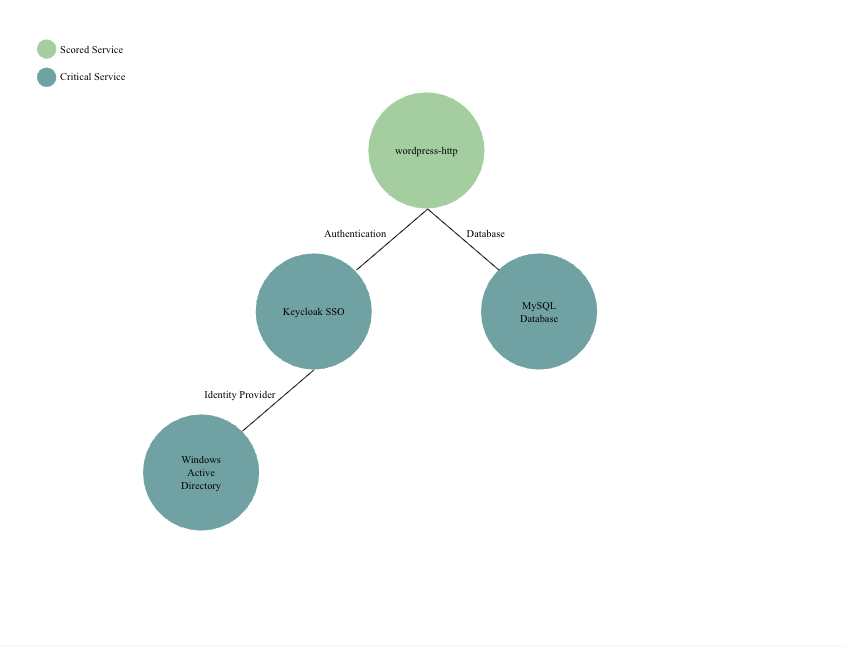

Your goal for perfect inventory should be to enumerate all critical services, which includes all scored services and their dependencies. To do this methodically, you can take a top-down approach. Investigate each scored service, find any dependencies it might have, and then follow that process recursively. An example might be a WordPress website that uses an AD-joined SSO solution for authentication and a separate database server.

As you can see in the example above, we identified four relevant, critical services, including the original scored WordPress website. Having this information is incredibly important, because it tells us what to investigate if the WordPress site goes down, what technologies may need to be secured, and what potential lateral movement paths exist.

While this is a mostly manual approach, you can still automate basic inventory tasks, such as identifying what operating systems are on your network, their preferred DNS servers, IP addresses, and more.

How To Inventory

Good inventory is a balance: doing the least work possible while still getting the information you actually need. This is tricky to cover in isolation, because how much inventory you need depends on your competition strategy and how much automation you have.

For example, if you’ve built scripts for multiple Linux distributions, it’s not enough to just know which systems are Linux or Windows, you need to know the specific distros. If your plan is to secure machines in a certain order (say, starting with the DC), then your network scan should also check for port 88 (Kerberos).

My advice: center your enumeration on priorities that must be solved through inventory. These may change during the competition, but some things will always be critical.

- Need to stop EternalBlue quickly? Run a scan for port 3389 (RDP) so you can identify Windows machines fast and patch them.

- Need to block Zerologon to prevent a domain takeover? Find the DC: scan for port 88, and check the DNS settings on systems you’ve already accessed.

- Planning to change domain user passwords immediately? Then you need to check which web services rely on DC binding, and which accounts are used, so you can update their bind credentials.

- Worried about an NGINX 0-day? Run a

curl --headagainst all web services to check headers and spot NGINX servers.’

The key is to size your inventory wide enough to cover everything that matters to your strategy, and everything that could blow it up. I know this might sound a bit contradictory to the flashlight analogy from before, but the point isn’t that your beam has to be wide at second zero. Instead, it should expand rapidly, within the first 15 minutes, so you’re catching critical services and unknowns before they catch you.

Automation

The ability to build automation is one of the most powerful capabilities teams are allowed in CCDC. Many of the top teams invest heavily in their automation and see clear benefits.

There are certain tasks that need to be performed on every machine, or tasks that are too time-consuming to do manually. For example, inventorying system information like IP, OS, and hostname is inefficient to do by hand. If a team uses the same SIEM solution every round, it makes sense to script its setup, including standing up the log aggregator and configuring forwarding agents on each machine.

A common pain point in automation is building tools that work across multiple operating systems. This is especially difficult for Linux tooling, since competitions often include a wide range of distributions, from Debian-based systems like Ubuntu to FreeBSD or Slackware, with some as old as 10–15 years.

The best approach is to build short, reliable scripts instead of trying to automate the entire competition. Focus on actions that work across most OSes and are critical to your minute-zero strategy, like changing the root/Administrator password, disabling SMBv1, or configuring Windows Defender. For UNIX systems, write POSIX-compliant scripts and avoid “bashisms” to maximize compatibility.

Another proven automation strategy is centralized execution tools that launch scripts across other systems over WinRM and SSH from a single machine. This significantly reduces overhead and simplifies operations. Not using this kind of automation puts you at a disadvantage, especially for high-overhead tasks like resetting default credentials across many servers.

Automation is key to winning CCDC. When you are already at a disadvantage, every opportunity to make the competition easier matters, and robust automation is one way to do that. Below are links to public centralized execution tools like Coordinate for Linux and Dovetail for Windows, as well as repositories from top CCDC teams. These links may change or become unavailable over time.

Centralized Execution Tooling

coordinate (author: sourque): https://git.sr.ht/~sourque/coordinate

Dovetail (author: altoid0): https://github.com/Altoid0/Dovetail

CCDC Team Repositories

University of California, Irvine: https://github.com/UCI-CCDC/LOCS

Stanford: https://github.com/applied-cyber/ccdc

University of Central Florida: https://github.com/HackUCF/SnoopyOnSecurity

Dakota State University: https://github.com/DSU-DefSec/ace

CalPoly Pomona: https://github.com/cpp-cyber/blue

This past season the finals event heavily restricted how and when we were allowed to deploy automation. It is possible that the regions will follow suit to some extent. However, automation was still very helpful during the finals and should still be a heavy investment for any team.

Team Composition

Team composition is often brushed off with advice like “everyone should know everything,” but that’s rarely practical. New teams, such as mine, have people join with zero cybersecurity experience. Instead of expecting them to know it all, we built roles around what each person could realistically learn and contribute. This also allows people to gain deep expertise in certain areas which is invaluable for injects and other challenges that may arise during competition.

Captainship [📖]

Team captain is a multi-faceted role, but at its core comes down to having the most awareness on the team. This doesn’t just mean awareness of teammates and during competition, but a deeper understanding of the competition itself and what it entails. Now, the responsibility of training and preparation doesn’t all have to fall on the captain, but in my experience as one, I was the primary strategist in terms of deciding major team objectives and planning out competition operations. While I don’t fully feel qualified to give exact advice on what a captain should be doing, I’ll instead provide what I did during the competition season and my justifications for certain choices I made. No two people will lead a team the same way, so I would suggest you build your captainship with my advice instead of modeling yourself after it.

Knowledge Requirements

As captain, I felt it was important for me to understand every major aspect of the competition, at least at a high level. I reasoned that it would be difficult for me to help manage my incoming Windows team, which was going to consist of two new students, without understanding it at a base level myself. In the same regard, I did my best to understand technologies that other team members specialized in, such as network firewalls or Kubernetes. Even if I didn’t fully understand how to deploy a multi-component application on Kubernetes, I understood the complexity of the service and the common pitfalls or vulnerabilities our team might run into. Essentially, having a broad perspective and understanding of the competition and what it entails was the core goal.

Personally, I was able to assume this role with the following background knowledge.

- Linux: I specialized in Linux for the six years I competed in CyberPatriot, and the previous year in CCDC.

- Windows: Bits and pieces from former teammates who did specialize in Windows, previously had completed the OSCP, and building Windows boxes for mock competitions throughout the year.

- Complex Services: Gained Active Directory knowledge by deploying AD servers for mock competitions, and Kubernetes knowledge from my time as linux lead the year prior, where I learned to create clusters and deploy basic services like Nginx.

- Corporate: Multiple internships in various areas of cybersecurity: Security Analyst, Security Operations, and Security Research. I learned a lot about the business side of cybersecurity and the understanding of balancing business value with security through real world experiences. Along with learning how to write several reports for upper management and also technical documentation.

- Blue Teaming: Multiple years of CyberPatriot and a previous year of CCDC. Many instances of completely failing to defend against red team, and some successes, taught me what works and what doesn’t.

- Red Teaming: OSCP, experimenting with and learning to deploy C2s, red teaming myself and my team, researching vulnerabilities to build into boxes, and staying close (virtually) to many people who specialize in offensive security.

I understand a lot of the experience I had going into captainship was due to unique circumstances, but the key takeaway is that any experience is useful. CCDC covers so many areas that knowledge in any one of them can make a meaningful difference.

Why Roles?

First, as I mentioned earlier, many teams include students who are new to cybersecurity, or even new to computing entirely. Expecting them to learn every discipline to the level required for competition just isn’t realistic. That’s why assigning roles works. It allows team members to focus their learning, develop relevant skills, and contribute meaningfully without being overwhelmed.

During my time competing, I found that roles purely for organizational and operational reasons were incredibly useful. For example, our team had not only “Windows”, “Linux” members, but also a designated “Windows Lead” and “Linux Lead.” These members had a couple of extra responsibilities within these roles. First, they were responsible for understanding the state of the machines they “owned,” so the Windows and Linux machines were always being tracked by someone with full awareness of their configuration, issues, and any changes made. This allowed me to make informed decisions quickly by asking the appropriate lead for a status update, rather than having to chase down information from multiple teammates.

Redundancy is also important, I won’t discount that. It’s important for multiple people to know certain things so that if someone gets bogged down, another team member can step in and take over their role or responsibilities.

Team Composition

Below is the team composition I used during my most recent year of competing. While every team will have its own unique structure, I believe all teams should follow the same core principles: assigning leads for major disciplines and building in redundancy wherever possible.

- Team Captain

- Corporate & Web Lead

- Linux Lead & Threat Hunter

- Windows Lead

- “Jack of all Trades” & Mock Competition Co-Organizer

- Linux & Networking Specialist

- Windows Specialist

- Corporate Specialist & Dedicated Writer

1. Team Captain

The responsibilities of the team captain are all-encompassing. Outside the competition, it involves hours of strategy, planning mock competitions, checking in with the three subteams, helping them decide priorities, and coordinating between them to reduce friction.

The captain can remain either hands-off or hands-on. At the regional level, we found a mostly hands-off captain useful. With so many moving parts, having someone maintain a big-picture view and track each subteam’s progress prevents disorganization.

The captain should delegate injects, weigh their importance alongside other tasks, and assign them accordingly. They should help write injects when possible, especially if technical members can only provide screenshots or limited notes. With their broad technical knowledge, the captain can write deliverables and is often the best person for network map or inventory injects.

At nationals, we switched to a hands-on playstyle for the captain. With a faster red team and simpler network, having all hands on deck was more effective. One mistake in the 2023–2024 season was keeping a hands-off captain at nationals, which left gaps in execution when the situation required direct involvement.

2. Corporate & Web Lead

The corporate lead is responsible for all business injects during the competition. They should understand the status of every inject, who it is assigned to, and how far along it is in terms of completion. They should also be writing whenever they get the chance, as their secondary job, when their web lead duties leave them with time.

The web lead is responsible for all websites or web applications during the competition. They should begin by scanning for websites, changing default credentials, and documenting everything they find. Oftentimes, these websites can provide insight into the competition scenario or be useful for later injects, so having detailed documentation becomes valuable. It’s also no secret that a majority of scored competition services are web applications, so having a solid understanding of them is especially useful throughout the event.

In many scenarios, the web services are the primary way customers interact with the company, so having documentation and oversight of them effectively is also important from a customer service (orange team) standpoint.

We found that both of these roles could be handled by one person. The web lead role is more demanding at the beginning of the competition when password changes and service identification are a priority, but tends to slow down shortly afterward. Business injects, on the other hand, come in slowly at first but ramp up significantly during the middle of the competition.

Outside of the competition, the corporate lead should ensure that any knowledge gaps and common injects are addressed. For example, WRCCDC tends to include a staple “install a SIEM” inject in every competition. The corporate lead should take the initiative in preparing the team for these types of injects and should also pre-write common injects whenever possible. In addition, the corporate lead should be well-versed in cybersecurity terminology and concepts. Seeing and being asked to explain topics like bug bounty programs, secrets management, data loss prevention, SOC compliance, or privacy concerns related to AI should not come as a surprise.

3. Linux Lead & Threat Hunter

Linux lead is responsible for all Linux systems during the competition. They must be comfortable with a variety of distributions, from Debian-based systems to BSD, and be the primary teammate deploying automation across machines. They maintain an overview of all Linux machines at all times: what security actions have been taken, what risks or vulnerabilities remain, and which machines may have been compromised.

Outside the competition, they prepare the overall Linux strategy and develop playbooks, reference guides, and automation to execute it effectively.

This role becomes relevant when the team can deploy a functional SIEM solution onto the network. The threat hunter manages the SIEM, monitors for malicious activity, and ensures logs from all machines are properly forwarded and ingested.

Outside the competition, the threat hunter should learn to manage the SIEM and build automation or playbooks for deploying logging across the network. They should work with both the Linux and Windows teams to develop detections for common indicators of malicious activity, such as failed logons or known exploits like DCSync.

Our Linux subteam was already pretty mature and often had free time during competitions. We used this to our advantage by giving the Linux lead a second role. That said, the role doesn’t have to belong to Linux. It can reasonably go to anyone with a broad enough understanding of the operating systems and network, maybe the Windows lead or a the jack of all trades.

4. Windows Lead

The Windows lead is responsible for all Windows systems during the competition. Similar to the Linux lead, they should know what security actions have been taken on each system, what risks or vulnerabilities remain, and which machines may have been compromised. This role requires a strong foundation in Active Directory and an understanding of the vulnerabilities commonly associated with it.

Again, just like the Linux lead, they should be primarily responsible for deploying automation across their systems. Between competitions, the Windows lead should be preparing the overall strategy they plan to use for approaching each event. This includes developing playbooks and automation to help them achieve their competition objectives, such as changing all user passwords or disabling SMBv1.

While the captain will help with this, the Windows lead should be highly cognizant of the fact that many services often depend on the Windows Domain Controller, which is a staple of CCDC competitions. Whether it is used for authentication or relies on the domain controller’s built-in DNS server, the responsibility is significant. The Windows lead should ensure, to the best of their ability, that they are accounting for all potential dependencies when securing their server.

5. “Jack of all Trades” & Mock Competition Co-Organizer

This teammate’s role is somewhat self-explanatory. They are a team member capable of fulfilling various roles during the competition — not necessarily to the full extent that the specialists can, but enough to fill gaps and support others when they are overloaded or dealing with particularly difficult tasks. During the competition they’ll often be placed on injects, curveballs such as unrecognizable services or systems, and assigned to support the operations of existing specialists.

What’s special about their role as a mock competition co-organizer is the level of work they put in outside the competition. Alongside the captain, they plan and help develop the mock competition environments between competitions. This includes hours spent deploying and configuring services, ensuring they are vulnerable, and making sure the network either closely mirrors the round they are trying to emulate or aligns with the intended learning objectives.

6. Linux & Networking Specialist

This team member specializes in Linux and networking. They should be comfortable working with a variety of distributions, from Debian-based systems to BSD. In regards to networking, they should have a strong grasp of TCP/IP topics, routing, and how to configure and deploy various firewalls such as PfSense, FTD, PAN, and more.

Outside of the competition they should be supporting the Linux team and working with the captain in regards to strategy, playbook-building, and automation development.

7. Windows Specialist

This team member specializes in Windows systems. They should understand the Windows ecosystem and be especially familiar with Windows-native services such as Active Directory, IIS, SMB, and others.

Both inside and outside the competition, the Windows specialist should support the Windows lead and captain in whatever is needed related to their area of expertise, whether that involves writing injects, developing automation, or handling any other Windows-specific task assigned to them.

8. Corporate Specialist & Dedicated Writer

The corporate specialist and dedicated writer role is fairly self-explanatory. They are responsible for writing and working on business injects throughout the entirety of the competition. With the heavy flow of injects during CCDC events, this role is nearly essential for addressing them effectively.

When not competing, they should focus on supporting the corporate lead and coordinating with the technical teams to pre-write or prepare for injects commonly seen in competition.

Insight Into Assigning or Advertising Roles

When running training for the competition before tryouts, we usually try to sort potential members into three major disciplines: Linux, Windows, and Corporate. During my time running training, I developed the following insight:

Linux vs. Windows

Many students want to join the Linux team right away. It often seems “cooler,” especially with heavy command-line use and the fact that most students never learn Linux in formal education.

However, we need Windows competitors, and Linux may not be the best fit for everyone. Linux competitors generally need a broader knowledge base to succeed, due to the number of distributions and variety of services in competition. Common Linux complexity comes from services like Jenkins, Kubernetes, Docker, and custom applications, along with distributions such as Fedora, BSD, and Slackware.

The Linux specialist role suits students who like learning many things at once. Windows environments tend to be more standardized, making them better for students who prefer to dive deeply into one area. Windows specialists should focus on core OS structure, nuances, and native services such as ADDS, ADCS, IIS, and SMB.

When assigning roles, I’ve found that highly aware students fit well into Windows roles, while students who can juggle multiple tasks and quickly grasp new topics thrive in Linux roles.

One way to quickly “sus” out who fits best in each role is to put new students through a mock competition. Students who, without being told, naturally listen to their teammates and base their actions on what others are doing are often a good fit for Windows. In the real competition, especially on the domain controller, Windows teammates affect everyone. They need to stay aware of the team’s state at all times to avoid costly mistakes.

On the other hand, students who can juggle multiple machines at once, help teammates while still finishing their own tasks correctly, or clearly communicate what they’ve tried (and what has or hasn’t worked) when handing off a machine or task, show the skills that are core to Linux-specific roles.

Corporate

The business inject portion of the competition is often the most overlooked, yet one of the most critical parts. It frequently accounts for at least half of the total competition point breakdown. It can be difficult to advertise because it seems like it’s just writing, and students often don’t realize how valuable those writing skills are when translated to real-world work.

In internships alone, I’ve often been tasked with developing technical blog posts, writing reports for non-technical executive leadership, documenting automation, and drafting software design documents. That experience has closely mirrored CCDC, and CCDC has helped sharpen those skills even further.

While this is completely out of your control, I’ve found that the best corporate members are often successful in part because of their previous experience. In the past year, our corporate lead was a PhD student specializing in software security, who brought a wealth of experience to the team. He was an incredible writer due to his background in research, and had a broad understanding of cybersecurity from previous internships in product security and security research. Our corporate specialist and dedicated writer also had relevant experience as an IT intern and a former service worker. This gave her the necessary background in working patiently with customers, along with enough technical experience to embed into her writing, and effectively communicate with non-technical individuals.

Jack of all Trades

This role is hard to assign, and if you do have one, it will likely be filled by a veteran member of the team. The student who took on this role for us was an incredible learner, with the ability to pick up new concepts very quickly. It is also a somewhat selfless role, as it often involves learning or being assigned to tasks and technologies that may not be personally interesting, but are necessary for the team to have some level of talent or experience in those areas.

When building teams year-by-year, it’s important not to stick exactly to last year’s roles and responsibilities, but instead build a new team capable of achieving the same objectives with new teammates whose roles and responsibilities are shaped around their strengths. This is especially important when you don’t have a large pool to choose from. We were lucky this past year to still have a small abundance of people trying out (about 20) so things went a bit smoother for us. If we were not choosing from a large pool, we likely would have made even bigger changes to our team composition to better accommodate the new skill distribution of the team.

Time Travel

Unless you’re a team that has been competing for many years, you likely have at least a couple of newcomers to CCDC on your team, possibly even students who have never touched cybersecurity before. It’s not controversial to say that CCDC is an incredibly overwhelming and involved competition. Every competitor, at some point, has faced the difficult circumstance of having to drop injects, fix multiple downed services, and deal with red team activity all at once.

When competing, I firmly believed that the first time any of my teammates faced this kind of situation should never be during a real competition. There needs to be a way to give new team members the experience of the veteran students on the team, without potentially sacrificing a real competition round. That’s what mock competitions are for. In a way, they’re like time travel. A well-made mock competition can give students the equivalent of years of experience within a single competition season.

My team’s use of and emphasis on quality mock competitions was our single most effective preparation strategy for CCDC.

Mock Competitions

In the 2024-2025 CCDC competition season my team and I developed eight mock competition networks, including the training and tryouts networks. This gave all team members years of experience that they could have never gained otherwise, giving us more in-competition experience than many of the older teams that we played against.

While the UCI CCDC team is 5 to 6 years old, we had lost much of the knowledge from the original team that went to Nationals years ago. Many of those alumni connections had faded, and what we did have left were outdated strategies and checklists that no longer held up in the current competition climate.

| Number | Networks | Boxes | Injects |

|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | EcoClean | 11 | 12 |

| 02 | Royal Retreats | 10 | 17 |

| 03 | Merger Mayhem | 9 | 19 |

| 04 | Pioneer Paradigm Labs | 8 | 4 |

| 05 | Risky Robotics | 9 | 3 |

| 06 | Let’s French | 5 | 5 |

| 07 | “It’s Over” | 29 | 9 |

| 08 | Zaps | 23 | 15 |

Totals:

- 8 networks

- 84 injects

- and 104 servers

Not only was the sheer number of mock competitions important, but quality was incredibly important to us as well. Each network was carefully planned and given a scenario, with many of them built to either mirror upcoming competition rounds or introduce challenges that I, as team captain, knew we were not prepared for or would likely struggle with.

When it came to building the mock competitions, most of the planning was done by me, as I had specific areas I wanted the team to focus on. I worked closely with our mock competition co-organizer to help build out the environments, and our corporate lead contributed by writing scenarios and adding realistic business injects. It was mostly veteran members handling the bulk of the work so that our newer members could get the best possible training experience. That said, we also involved the rest of the team in parts of the mock-building process. I believe that learning how to build vulnerable systems is a valuable skill that not only helps develop technical intuition, but also translates directly to performing better during the competition.

Mock environments were also incredibly useful after the fact. They gave us a way to test our automation across multiple networks and scenarios. Since automation and CCDC strategy is all about ensuring consistency and adaptability across a wide range of environments, having diverse, repeatable mocks helped us validate that our tools and approaches worked reliably — not just in ideal conditions, but under realistic and varied setups.

We had a beefy Proxmox server that hosted all our mock environments. It was large enough to store several networks at once and even run multiple simultaneously. Whenever we wanted to practice, we just reverted an environment back to its pre-mock state and powered the virtual machines on.

Below I’ll provide some screenshots and insight into some of our most useful mock environments.

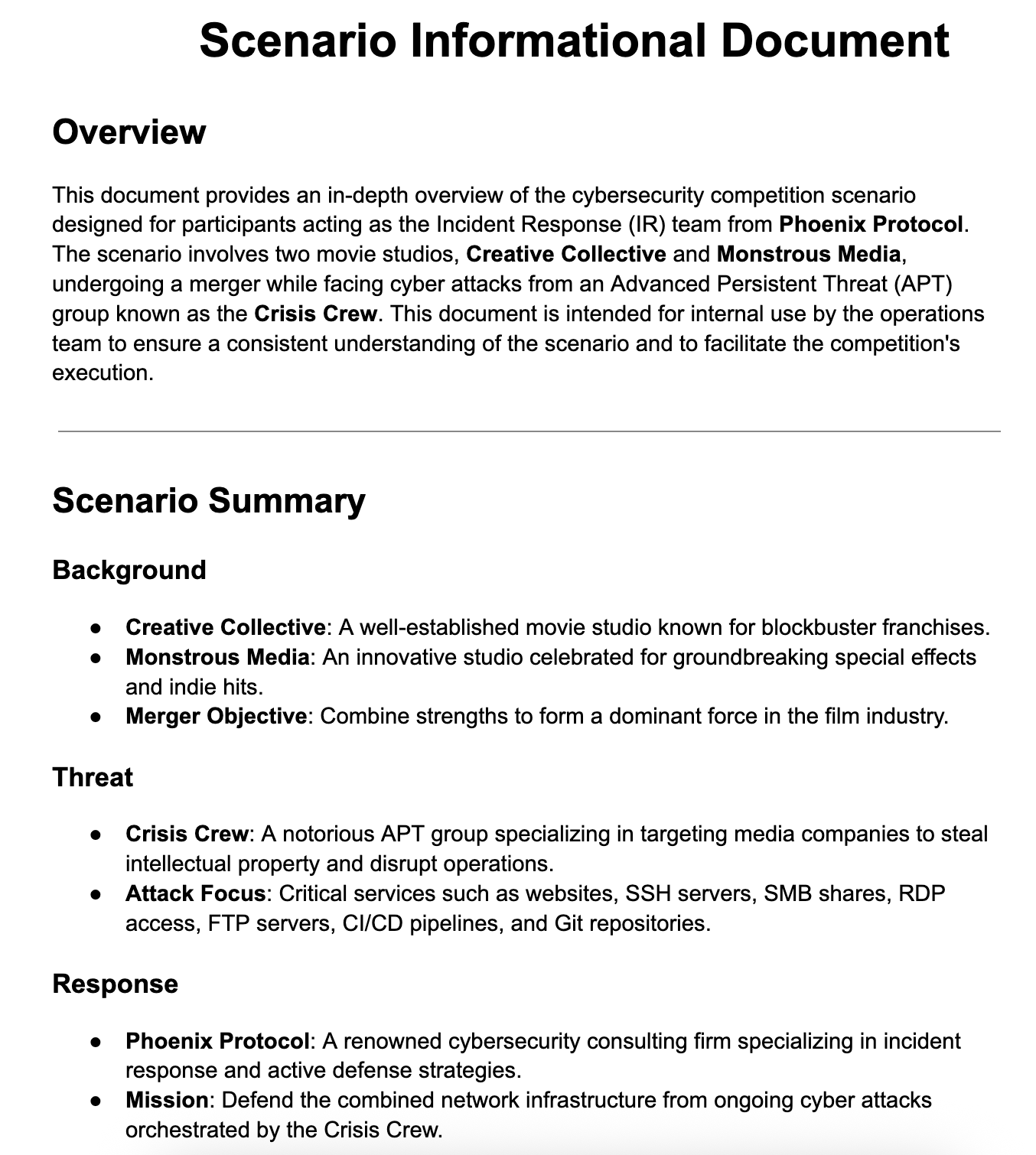

Merger Mayhem [📖]

Merger Mayhem was our tryouts network to help decide what students would be selected for the 2024-2025 competition season.

Merger Mayhem involved a scenario inspired by the 2024 CCDC finals event, with two film studios being attacked in the middle of a merger. This competition had a complex scenario, with blue teams being part of a security consulting program that was brought in during a cyber-attack in the middle of the merger. Students had to juggle injects that were from all three companies, while also securing two networks with separate domain controllers. This network was incredibly difficult and the competition had an active red team as well. Both teams had very low scores, but our goal was to see which students were able to remain calm under pressure and put their best foot forward.

After the event, the team used this network numerous times to practice the potential scenario of having multiple domain controllers during a competition.

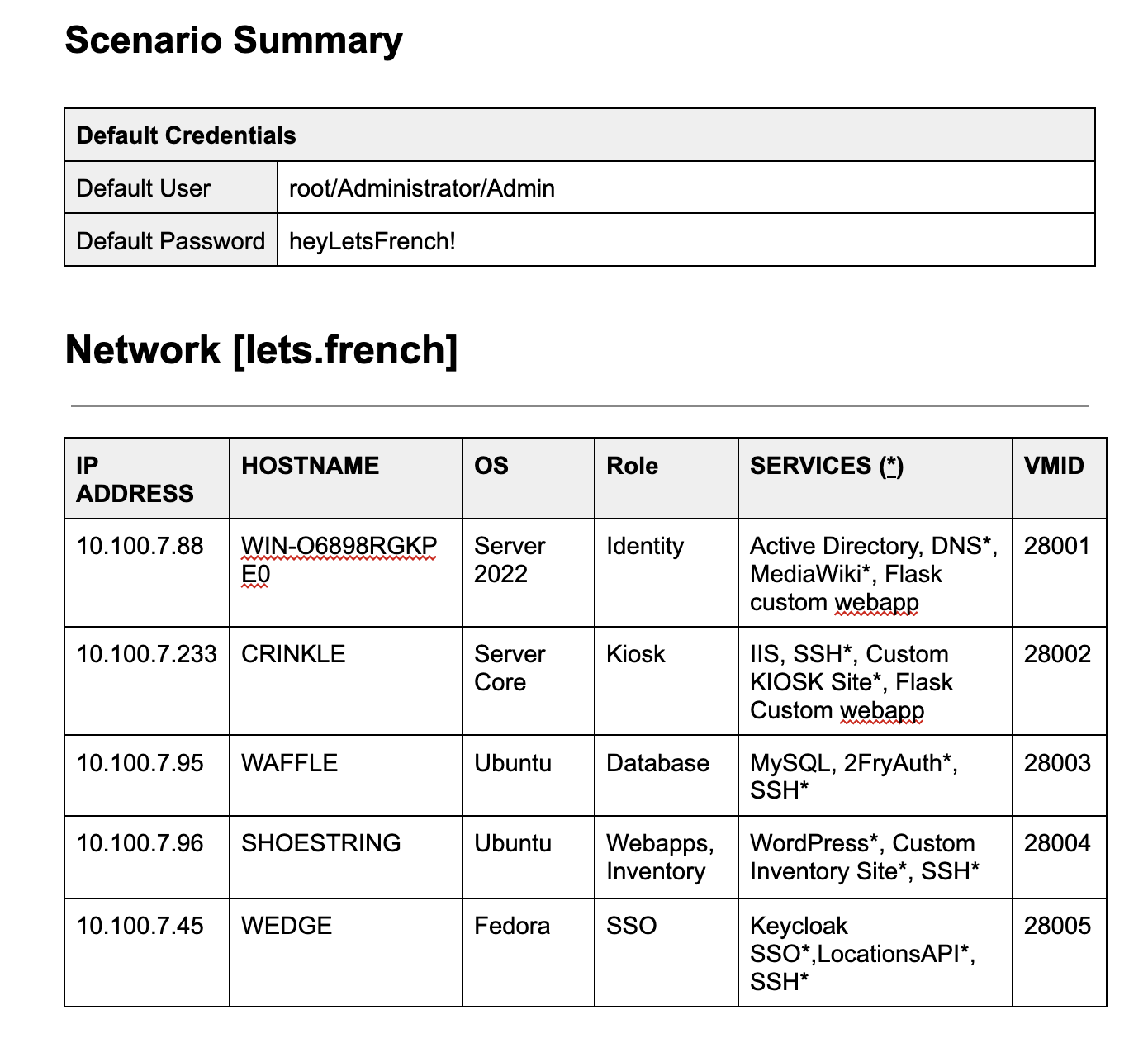

Let’s French [📖]

Let’s French was a smaller competition network built during the preparation for the WRCCDC regional finals.

Let’s French was a build-your-own French fries restaurant, not unlike Chipotle in structure. The mock network was filled with custom services and included Windows Server Core, both areas we had struggled with during the qualifiers and invitationals competition rounds.

This network was later used in combination with our Risky Robotics network, another environment we developed in preparation for the qualifiers, to practice our strategy across multiple networks in parallel, since we anticipated seeing that setup in the regional finals round.

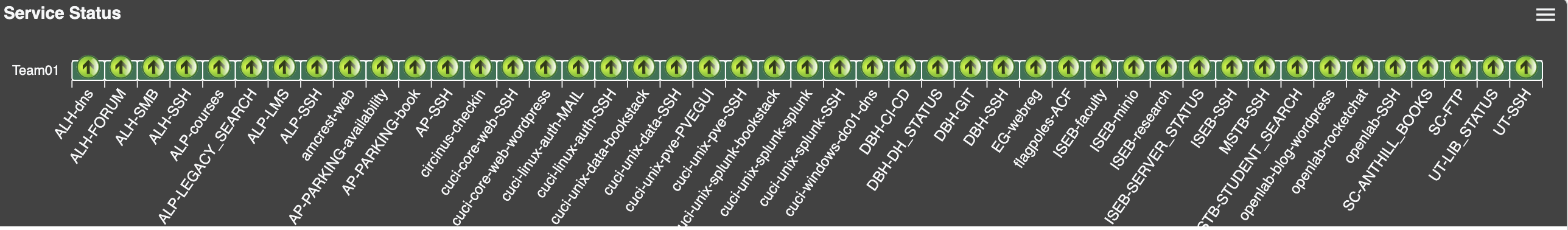

It’s Over [📖]

The It’s Over network was the most ambitious environment we created, designed to mirror what we anticipated the regional finals would look like. This network alone took over a month to build and included nearly everything we expected, from a “private cloud” environment to on-premises servers, hypervisors, a web camera, physical networking equipment, and more.

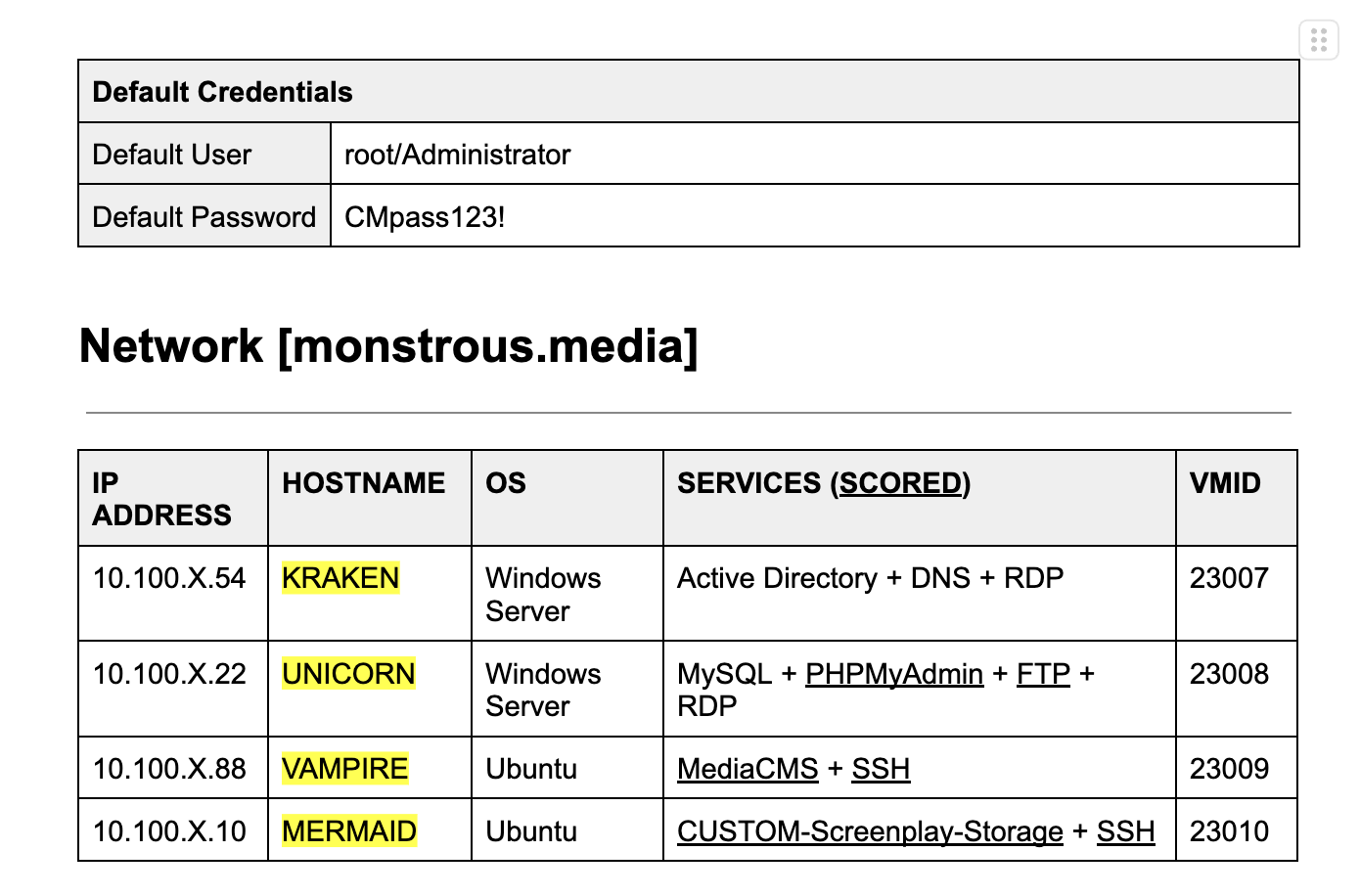

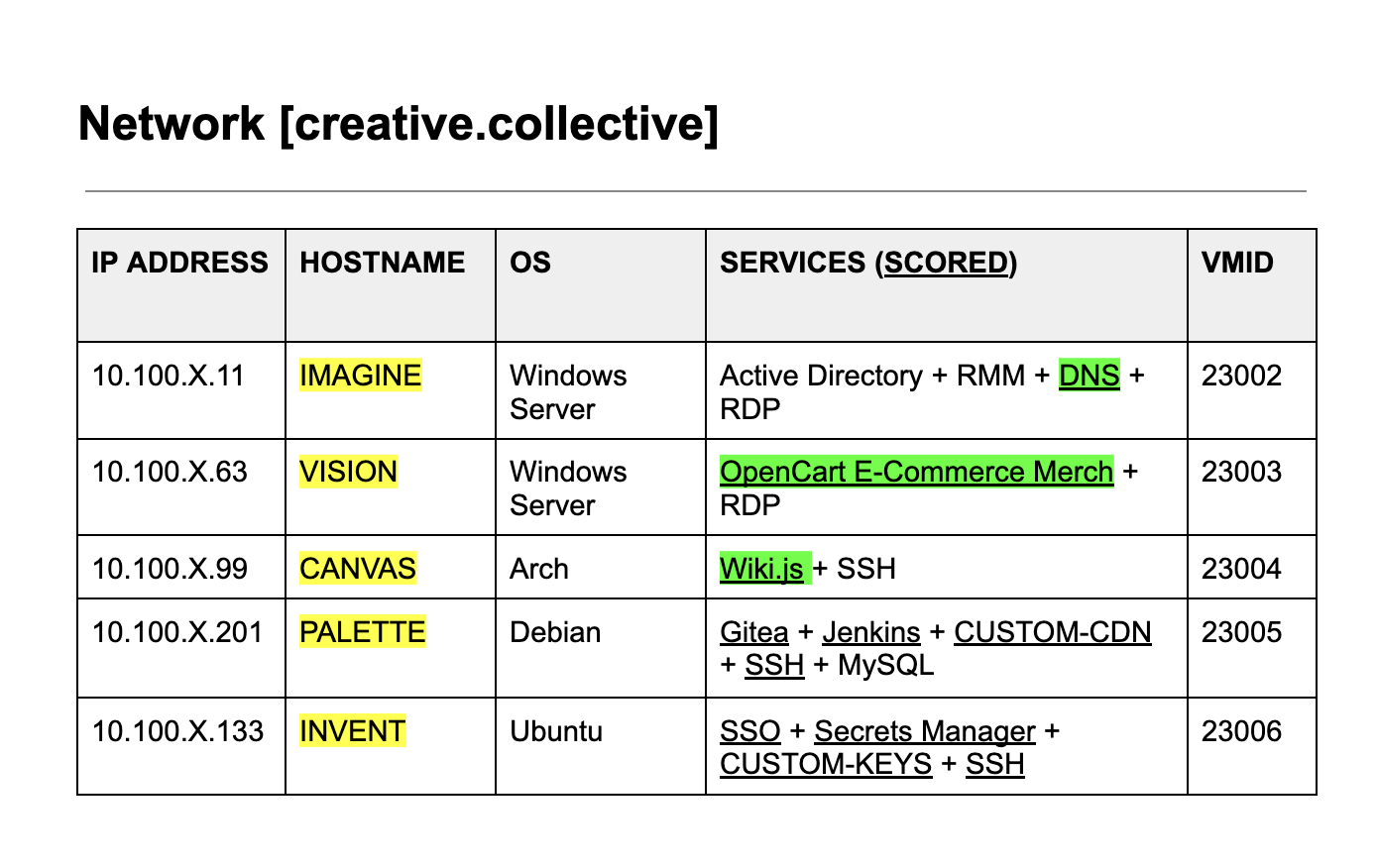

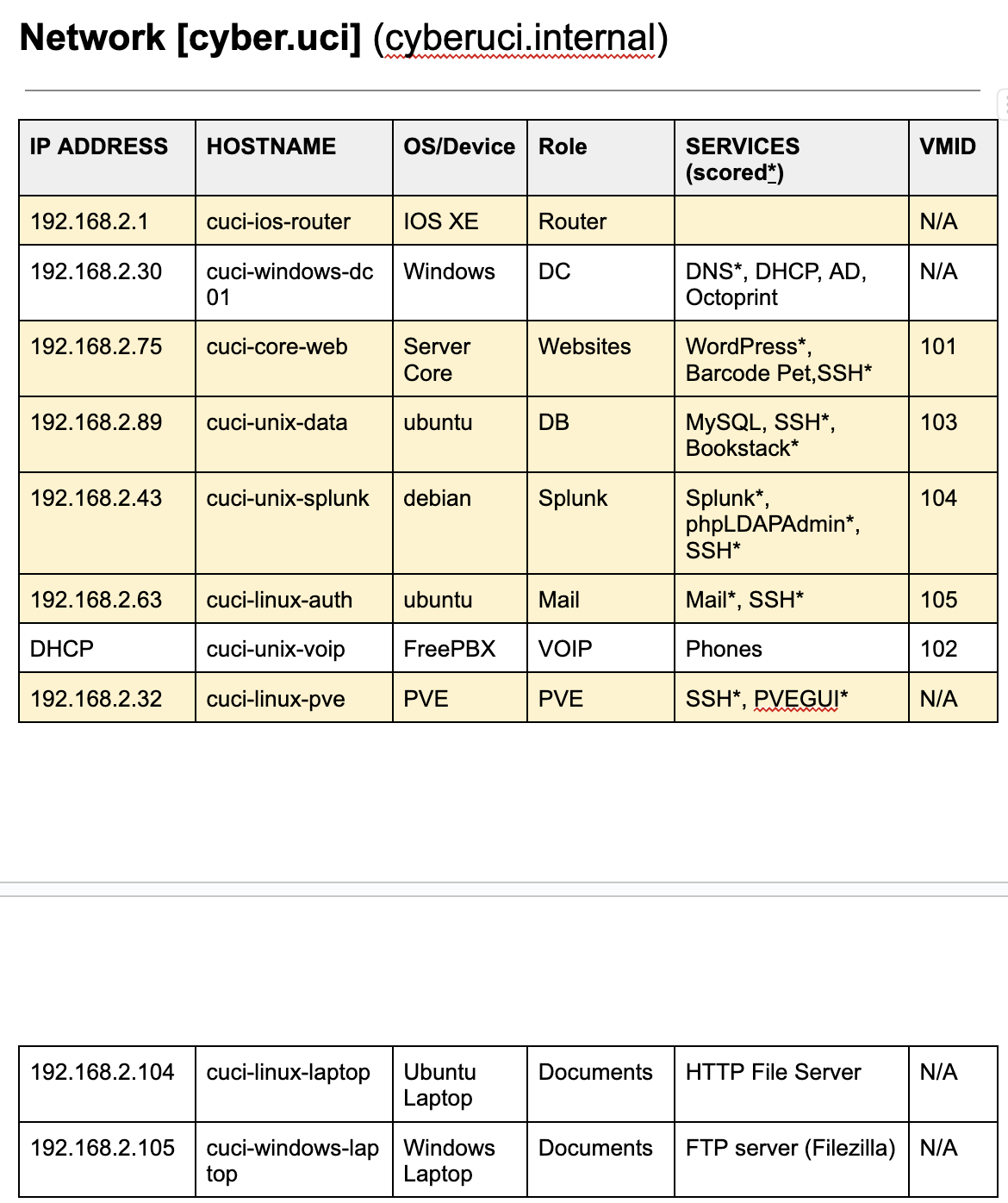

Network documentation for the It’s Over mock

The sheer number of scored services on the scoreboard for this mock competition

When we ran our final mock competition before regionals, we used this network alongside being attacked by a red team that employed tools, exploits, and C2 frameworks we expected to see during the competition, such as CrackMapExec, Zerologon, Cobalt Strike, Sliver, and others.

The red team was made up of my personal connections and club members or alumni. If you can’t organize a red team for yourselves, I’d suggest implanting C2 beacons or other persistence measures beforehand. After your mock, test whether those, along with other attack vectors like EternalBlue or exposed databases, are still available. Bonus points if you pause every 15 minutes to check their status over time. Even more bonus points if you automate that process

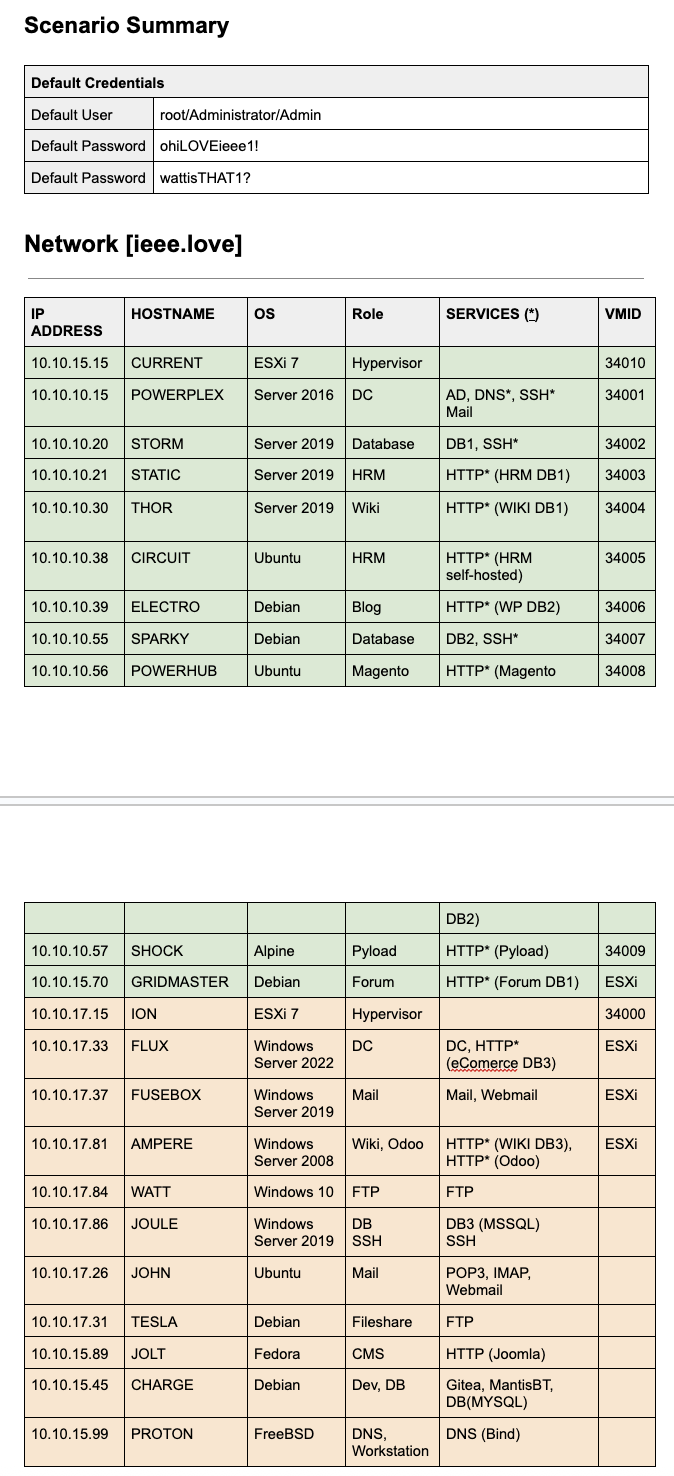

Zaps

The Zaps network was built to closely mirror the National Finals environment. It’s no secret that the NCCDC network doesn’t change much from year to year, so we did our best to replicate that network as accurately as possible.

We ran eight mock competitions using that environment, without a red team, focusing solely on practicing the first few hours of the competition each time. Our goal was to make sure our minute-zero strategy was as close to foolproof as possible.

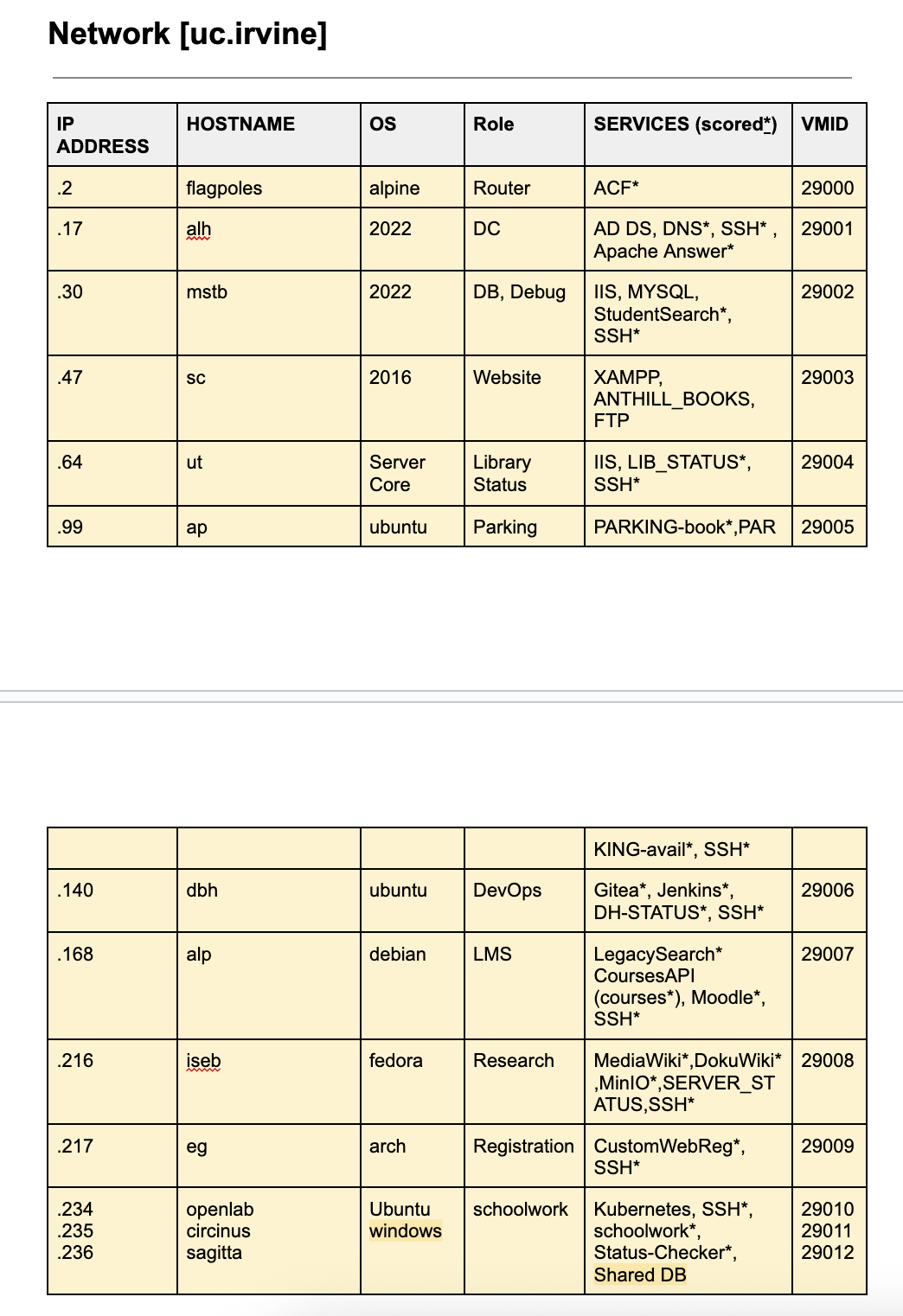

Network documentation for the Zaps environment

Subteam Autonomy

Each subteam: Linux, Windows, and Corporate, worked largely independently toward completing major objectives defined by the captain. These objectives included high-level goals such as “ensuring minute-zero was smooth and automated as much as possible” or “being fully prepared for any SIEM or centralized logging injects.” Within those boundaries, each subteam was responsible for planning their approach, building the necessary tooling or documentation, and holding themselves accountable for progress.

This autonomy allowed teams to stay focused and move quickly without constantly needing approval or guidance from the captain or other subteams. The Linux team could iterate on hardening scripts and automation, the Windows team could dive deep into AD and credential rotation tooling, and the Corporate team could refine their inject tracking and writing process, all in parallel.

Full-team meetings and mock competitions served as checkpoints. These were used to test the cohesion of our systems, address any friction between subteams, and iterate on our priorities and objectives based on what did or didn’t work. After each mock or sync, every subteam would return to their own work with clearer goals and sharper focus for the next round.

Nightmare Scenario

Something I regret not doing more during our mocks and practices is putting the team through a “nightmare scenario.” When everything is crashing and burning, it becomes easy to forget basic principles and difficult to stay level-headed, which leads to avoidable mistakes and lost points for no good reason.

A nightmare scenario looks like a mock competition where the team is given borderline or even outright impossible challenges. This might include a red team with fewer rules of engagement than usual, a network filled with unrealistic dependencies and services, or three to four major injects per hour. Basically, anything that can push the team to its breaking point and force everyone to think under pressure, make mistakes, recover from them, and learn how to keep moving when everything goes wrong.

I feel as though I didn’t have our team practice this enough, especially under pressure from an aggressive red team. We paid the price for it at Nationals, where a mix of bad micro-decisions, made individually by teammates while we were getting absolutely pummeled by red team on day one, ended up costing us.

The Perfect Mock

There is no “perfect mock” but not all mocks are created equal. Mock competitions should be approached in different ways and should have a clear objective by the end. Here are some examples.

Consolidation Mocks

Most of the mock competitions we ran were something I called “consolidation” mocks. These mocks happened on average every two weeks and were used by the subteams to test what they had been working on in the weeks prior. But it’s important to note that these were not supposed to be the first test of a subteam’s strategy. Each mock had a specific goal (for example: complete minute-zero successfully, complete minute-zero and post-minute-zero within a set time, or complete both while handling specific injects without a disastrous failure).

I strongly encouraged each subteam to fully test their strategy on a network beforehand, well before coming to the mock. It was already difficult to get all eight people together for two to three hours to compete, so that time needed to be reserved for fixing friction between subteams — not spent resolving internal subteam issues that could have been caught earlier.

Almost every one of these we ran was limited to simulating the first two or three hours of the competition. We found there were diminishing returns in trying to simulate anything beyond that, since the only parts of the competition that are mostly consistent and can be planned for are those opening hours when you execute your minute-zero strategy.

I also chose not to include an active red team or orange team in these, mainly because we didn’t have the resources to simulate them every time. More importantly, introducing red or orange team activity would have interfered with our ability to test whether our tooling, automation, and early-game procedures worked cleanly out of the box. Removing those variables allowed us to focus on system readiness, execution order, and technical skill consistently without disruption.

Simulation Mocks

While most of our efforts focused on consolidation mocks, we also ran a smaller number of what I called “simulation” mocks. These were longer 6–7 hour mock competitions that included multiple injects and an active red team. We typically scheduled a simulation mock about a week before an actual competition, after at least one consolidation mock had already been completed.

The purpose of a simulation mock was straightforward: to get the most accurate assessment of our team’s readiness and strategy in a setting that closely resembled the real competition. These tests helped surface any remaining gaps in planning, communication, or technical execution that we might not have caught during shorter, more focused practices.

Feel-Good Mocks

I would try to run a “feel-good” mock just a couple days before each competition. These were short, usually only 2–3 hours long, and ran on a network we were already experienced with through previous consolidation and simulation mocks. There were little to no curveballs in terms of injects. In these mocks we were generally well-prepared, and the entire goal was to succeed.

While these mocks may not have been strictly necessary, I felt they gave the team a much-needed sense of peace in the final days leading up to competition. CCDC is a high-stress environment, and it’s easy to get overwhelmed or make mistakes when you’re nervous or unsure. And because success in CCDC often comes down to making the right decisions at the right times, nerves alone can be disastrous.

These “feel-good” mocks almost always ended on a high note. We’d get through our minute-zero plan cleanly, complete injects on time, and walk away with confidence. Ironically, the only time one of these mocks didn’t feel good was the day before the National Finals. We never got our plan working 100%, and that left a bad taste going into the competition.

Know Your Enemy

While your enemy in the bigger picture might be the other teams, during the competition itself, it’s the red team you’re up against. Competing without a solid understanding of how CCDC red teams operate and what their objectives are is like playing blind. It will leave you unable to operate effectively against them.

Adversarial Mindset

You have to understand what the red team wants. They gain points in two to three ways, which may vary depending on the region. But generally, they score (against you) by gaining access to your systems, stealing PII, and at Nationals, earning points for persistence.

For the most part, achieving these objectives becomes exponentially more difficult for the red team as the competition progresses, especially when it comes to establishing persistence. At the beginning of the competition, there are exploits that result in unauthenticated RCE galore and default credentials for high-privileged accounts everywhere.

A lot of teams come into the competition expecting to defend against the red team by importing massive GPO templates, carefully auditing AD privileges, or hunting for SUID files. But red team starts with the low-hanging fruit, because they want the same thing as you: fast access and an easy path to persistence. That usually means getting the root account or another privileged user. Once they have that level of access, it’s easy to exfiltrate PII from PDFs or other data scattered across the system. In the same vein, there are default credentials on databases across the network that also contain swathes of PII.

As mentioned earlier, they will go for attack vectors that are low attack complexity and high impact, so make sure your strategies are focused around mitigating those vectors.

Playing to Your Strengths

In the competition, you are severely disadvantaged, and that’s by design. If you weren’t, it would be far too easy. Another unique aspect of CCDC is that each round can feel like a completely different competition. Qualifiers feel entirely different from Regionals and demand a completely new strategy. The same is true for the shift from Regionals to Nationals.

While adopting a new strategy and learning new skills between rounds is necessary, sometimes it is also important to stick to what has worked for your team and what you’ve become comfortable with.

Make The Competition Work for You [📖]

It’s clear that every region has its own style. SECCDC is notorious for its aggressive red team and machines that come pre-planted with malware. NECCDC is typically hosted in AWS and places a strong emphasis on Kubernetes. And then there’s WRCCDC, known for its focus on complex services like SSO, Kubernetes, CI/CD, and more.

For every team, the path to Nationals begins with winning their own region. Because of that, I believe many teams, ours included, optimized specifically to win their region. For WRCCDC we focused on speed and prevention, building powerful automation tools like blaze. We also tailored our practice and strategy around seasonal staples, such as the Alpine network firewall.

Once we qualified for Nationals this past season, we quickly realized—just weeks out—that many of our strategies wouldn’t work. The competition rules would not allow us to use automation from flag drop, and we wouldn’t be given a network firewall at all. The only one available was a pre-installed, but not deployed, Palo Alto Networks firewall.

We began our preparation by attempting to shift our entire strategy around this new competition paradigm, which led to a lot of confusion and discomfort. We struggled to operate with the same level of efficiency we had before, and everything felt slow and sluggish. It felt like we were losing the core of our strategy, and morale began to slip. About two weeks before the competition, we decided to reintroduce the core elements of our WRCCDC plans into our strategy for Nationals. Specifically, this meant using remoting technologies and utilities like WinRM and sshpass to deploy scripts and execute commands across the network from a single machine. Instead of using tools like Dovetail and Blaze to do this, we opted to work directly with the underlying technologies. Rather than learning to deploy the PAN firewall or avoiding it altogether, we chose to practice deploying our own version of the Alpine firewall. We eventually got the setup time down to under 15 minutes. As soon as we re-incorporated these elements into our approach, we felt a greater sense of control. We knew it might not be the optimal strategy for Nationals, especially considering how much more aggressive the red team would be and how much more hands-on work the Alpine firewall would require compared to PAN once deployed. But we were more comfortable with this approach, and that’s what mattered. Nationals is a game of execution, and the more comfortable we were, the better we could perform.

While this approach worked for us, I’m sure that if you managed to play Nationals with a strong emphasis on incident response and by using the PAN and other technologies as intended, you could outperform the other teams. However, at the time, it didn’t make sense for us to go that route. With the limited time left before the competition, we didn’t feel comfortable taking that leap.

My Experience [📖]

I don’t want to pretend like I know everything about CCDC or exactly how to win it. A lot of the strategies I mentioned above worked for us, but I haven’t won CCDC multiple years, so I don’t know how well they hold up over time. I also happened to win in a year when the rules changed considerably and the finals were held online. That said, I do feel like I’ve seen a lot of common pitfalls when talking to other CCDC teams, especially when it comes to training and overall philosophy. I hope that some of the things I shared above can help in some capacity.

Concerns Regarding CCDC [📖]

CCDC has been one of the highlights of my college experience so far, and I’m grateful for the friends I’ve made and the experiences I’ve had as a result. That said, there are aspects of CCDC that I believe could be improved. Many of my critiques below will be limited in their applicability to WRCCDC, as that’s the region I competed in. Some of the problems I mention don’t have a clear solution, but I hope to spark discussion within the community about how they might be addressed.

I also want to say that I am incredibly grateful to the competition organizers for volunteering massive amounts of their time to help build this competition. I understand the amount of time and effort these things take and I do not think of that lightly. I do not want to bash on any organizer or CCDC itself, but rather provide constructive criticism from my perspective as a competitor.

Artificial Difficulty

CCDC competitions sometimes struggle with introducing artificial difficulty. As teams improve year over year, there is pressure on organizers to increase the difficulty of the competition in order to better differentiate the best teams from one another.

In the effort to make the competition more challenging, some of the technologies or concepts introduced can feel arbitrary and even contradictory to learning, which seems to go against the core purpose of the competition. Some examples are below.

WRCCDC Invitationals #3 - Misleading System Hostnames

- Every system had a hostname that did not match its actual operating system. For example, an alpine machine was named WINXP.

- This made communicating between team members very difficult and unnecessarily confusing. I’m sure less experienced teams felt worse.

WRCCDC Invitationals #3 – Overly strict domain controller policies

- Group policies made it practically impossible to manage the DC directly.

- This disadvantaged newer Windows team members who wanted hands-on experience. For an event that should be focused on accessibility and learning, this felt counterproductive.

Qualifiers and Regionals – Esoteric or gimmicky operating systems

- Hannah Montana Linux, Slackware, and during Regionals, a system entirely in Papyrus font.

- While rare systems exist in the real world, introducing them in CCDC distracts from core principles. This also creates more setup work for organizers and breaks red/blue team tooling without meaningful skill development.

In short, I believe sometimes CCDC falls into the pitfall of making things harder just for the sake of making them hard, rather than trying to truly challenge students in a realistic environment.

Too Much SRE

A common problem I see with the competition, and this varies by region, is that many times the competition seems like it is more focused on the services and their configuration/deployment than the actual security aspects. More than half the time we spent training and competing was spent on learning to deploy, debug, and maintain services rather than learning actual security techniques and tooling.

While I do understand the value of learning to manage and configure services, I think there are many times that it takes away from the “Cyber” part of this competition. The time lost to debugging deployments and completing SRE-esque tasks could be better spent on learning actual cybersecurity techniques and tools.

I think this could be simply solved by limiting or completely eliminating “deployment” injects as my team liked to call them. Injects we received such as the following were, in my opinion, unnecessary:

Install/Implement (IDS, SIEM)

While I understand and appreciate the intent behind including an IDS or SIEM in the environment, I believe the focus on installation may not be the best use of time during the competition. In many cases, the installation step can be unnecessarily time-consuming, especially when teams run into memory or disk space constraints. This often delays or prevents students from reaching the more meaningful part of the task, configuring the solution to reliably detect malicious activity.

There is significant educational value in tuning and documenting IDS or SIEM configurations, and those are the skills that align more closely with what’s expected in real-world security roles and job interviews. In my opinion, this inject could be effective if the IDS or SIEM were pre-installed, allowing teams to focus on configuration, documentation, and justification of their changes.

This approach would ensure more teams engage with the core learning objectives, rather than getting stuck on initial setup challenges that may not reflect their understanding of detection and response.

Deploy [___] (e.g. Network Printing Service, File Dropbox, Rocketchat, VPN, VNC)

These injects may have limited value in a security-focused competition. While they can help students practice writing technical documentation, they don’t directly reinforce core security skills and may take time away from more impactful learning opportunities.

A more effective alternative could be to center the injects around securing or auditing these services rather than deploying them from scratch. For example, instead of asking teams to deploy a file dropbox, the inject could ask them to scan an existing dropbox for sensitive information such as PII, or to audit its permissions and access controls. This would offer a more security-relevant experience while still reinforcing documentation and communication skills.

On the flip side, here were some of the best injects I saw during my time competing, and what I think we should have more of:

Create an Infographic for [___] Phishing, CyberAttack, etc.

I really love the Infographic injects. The ability to communicate cybersecurity concepts to everyone, an important part of any mature security program, is an underrated skill. CCDC has definitely helped me build that, and I will be forever grateful for it.

Bug Bounty Program Implementation

This inject introduces several real-world security concepts and encourages students to think critically and methodically about vulnerabilities. I believe it challenges them to consider how vulnerabilities are discovered, reported, and prioritized based on risk and impact. One thing CCDC does well compared to more traditional competitions is introducing the soft skills in cybersecurity. More injects like this would strengthen that aspect of the competition.

Today’s Top 10

This inject required us to report two different “top 10” lists: the first was the top 10 IP addresses that sent the most traffic into the network, and the second was the top 10 that sent the most traffic out of the network. The inject also asked for the tool or method used to conduct the assessment. I think this is a perfect inject for a network security competition and should become a staple going forward.

However, my one concern is that there should be some form of basic network logging already configured before this inject is given. Otherwise, only teams that planned for it ahead of time will be able to complete it effectively and gain the full learning experience. This is a security-relevant inject, and all teams should have a fair opportunity to engage with it, regardless of their current standing or setup in the competition.

It’s Inaccessible

CCDC is impossible to play without the right resources and background. To do well, you need to fundamentally understand a lot of IT concepts and have real-world IT experience. Not only that, but to effectively prepare, you need access to a hypervisor so you can deploy practice virtual machines and build mock environments. Summarized well by my teammate: “How do you practice for a competition based around working on a mock corporate environment, without one to practice on?”

That barrier is already huge and likely deters a lot of teams from playing. If you’re not able to build mock environments, then your first time truly seeing what the competition is like will be during the competition itself. And at most, you’ll get eight hours to explore the environment, while you’re stressed, overwhelmed, and not really in a position to learn. After that, you’ll never see that environment again.

WRCCDC combats this to some extent with their Invitationals, low-stakes events that give teams a chance to see what the competition is like, but otherwise, most teams never get that opportunity.

First, you need basic computer literacy, and I’ve seen freshmen CS majors who don’t know what a file path is, or sophomores who can’t clone a repository. Then you need to understand server-client relationships, something that is rarely emphasized in school. After that, you need to learn basic terminal commands, and get fluent enough to RDP or SSH into a machine. But before you that, you need to grasp what a virtual machine is, how to deploy one, and how to do that with your limited resources.

Once you get past that, you still have to learn the operating system you’re securing. Want to setup firewall rules? You’ll need to learn networking basics: ports, protocols, subnets and more. Then you go back the firewall, test your rules with other command-line tools that you may not have yet learned to see if you actually blocked SMB or not.

It’s a long list of compounding concepts, a full package of IT understanding, that is required just to even get started in CCDC. That’s a major problem, because CTFs are far more accessible and don’t have this issue. You can open a browser or run a single nc command and start solving beginner challenges in under a minute. There’s no setup overhead, no barrier to entry, and no prerequisite knowledge that spans multiple technical domains.

Even for teams that do have access to resources like a hypervisor, they’re still at a massive disadvantage if they don’t yet have the skillset to build their own environments. WRCCDC does host past environments on their archive server, but they’re provided with little to no setup instructions, no details on which services are scored or how scoring works, and are designed specifically for WRCCDC’s (now former) ESXi environment. This is not useful nor helpful for newer teams who may only have a basic Proxmox server or are just getting started. Having the right hardware is not enough. The lack of clear documentation or guidance makes it much harder to learn, experiment, and improve.

While I understand that what I’m describing is a challenge inherent to cybersecurity itself, and that security professionals need to understand a broad set of technologies and concepts to do their job effectively, how can competitions like CCDC still expect to warmly invite newcomers if this is what they’re facing? There needs to be an honest discussion about how we can make CCDC more welcoming and accessible for new teams. Whether that means providing better documentation or pre-configured lab environments something has to change if we want to grow the community and make sure everyone has a fair shot at learning.

Further Reading & Inspirations

I read many blogs during my time competing and the insights I gained from each were fundamental to me and my team’s success. The following were the ones I went back to the most and I strongly suggest reading them if you find the time:

CCDC Nationals — Reigniting The Legacy

https://altoid0.com/ccdc-nationals-reigniting-the-legacy

Tanay “Altoid0” Shah, a two-time CCDC runner-up (2023 & 2024), wrote about his first year competing in CCDC and the lessons he learned along the way. He has earned a strong reputation with the National CCDC Red Team, who even gave him their badge after the competition in recognition of his skill.

Tanay is also the creator of Dovetail, a PowerShell-based remote execution tool that runs scripts in parallel over WinRM. We used it extensively throughout the season, and it played a key role in speeding up our team’s operations and response times.

CCDC Nationals in San Antonio, TX

https://sourque.com/events/ccdc/

Shane “sourque” Donahue, a 2022 CCDC runner-up, wrote about his experience competing in CCDC. What was especially valuable in his write-up was the detailed breakdown of the injects he encountered at Nationals, along with his reflections on why he believed his team came up short. His honesty and insight make it an insightful read for anyone serious about improving in CCDC.

He is also the author of Coordinate, a Go-based CLI tool that runs scripts over SSH on many remote servers. Coordinate was the inspiration for my team’s own tool, blaze, and has been used extensively by both blue and red teams at the National Finals.

LEGACY: 400 Days

https://gabrielfok.us/competition/400-Days

Gabriel “baseq” Fok, a 2023 CCDC runner-up, wrote a detailed article about his CCDC journey and how he led his team from struggling to qualify to placing second in the country. His insight was especially valuable to me as a captain. It helped me feel more confident heading into unfamiliar parts of the competition, especially the year before when I was competing for the first time and didn’t know what to expect. He explained both the regional and national levels of the competition clearly, and his perspective made a real difference in how I approached my role.

NUCC

NUCC is the National Upcycled Computing Collective. They do amazing work collecting old servers and other equipment from companies that are about to throw them out. Based in the SoCal area, they have been distributing computing equipment to various schools locally and beyond. Some of the schools they have helped so far include:

- University of California, Irvine

- University of California, Davis

- California State University: Fullerton

- California State University: Long Beach

To contact them you can first reach out to Steven Ngo (Discord: stengo)

Closing Thoughts

Being deep in the CyberPatriot community in high school, I had heard a lot about CCDC before I ever even got to college. I knew it was a hundred times more challenging than CyberPatriot, and I was excited to try it for myself. After playing CyberPatriot for seven years, I was ready to dive into something new.

When I first started, I never believed I would win CCDC. I thought that even making it to Nationals would be a long shot. I knew how fierce the competition was between the schools I had only heard whispers about schools like UCF, Stanford, DSU, CPP, and others. I spent many sleepless nights preparing and many hours “scheming” as my old captain would say, and doing everything I could to win. Coming from a high-performing CyberPatriot school, I wanted to prove that I could build at least a fraction of that same success with a not-yet-established group. I’m proud of what I was able to accomplish, but none of it would have been possible without the support of NUCC, my teammates, and my friends and family.

I will no longer be competing in CCDC, a decision I made early in this season. I plan to keep exploring cybersecurity in other ways, and I believe there’s a lot more to discover outside of it. I’m not sure how useful my insights will be to other CCDC teams, but this is my attempt to leave something behind for newcomers to follow. I truly love CCDC and what it’s done for me, and I want nothing more than for others to have fun, grow, and learn from it as well.

I would like to thank the following people for reading and providing feedback on this post.

- Katelyn

- Safin

- Steven

- Jacob

- Tanay

- Kristen

- Charles

- Dhruv

- Eric

- Chris

If there are any questions don’t hesitate to reach out on Discord (handle: hyper.nova). Thanks for reading.